This election has been so cerebral and comprehensive a contest of ideas, it probably seems churlish to suggest some policy alternatives have not been sufficiently explored*. Still, with both major candidates and wings of their parties now opposing proposed free trade agreements and calling for tougher enforcement and/or renegotiation of existing pacts, it’s worth considering what happened the last time the US adopted a protectionist policy, and what alternatives exist to deal with the negative consequences of international competition for segments of the workforce.

Briefly, the Smoot-Hawley Act of 1930 helped to usher in an era of tariffs and trade barriers between nations. Within a few years US trade with the world (imports and exports) declined by more than fifty percent. The American economy’s dependence on trade was and is limited, so there’s some debate as to the degree this contributed to the Great Depression, but few economists would argue it was helpful. Additionally, cycles of retaliatory protectionist actions amongst the Great Powers quickly spiraled into trade war, adding to a global atmosphere of rising jingoism and nationalist resentment whose denouement at the decade’s end was arguably the greatest catastrophe in human history.

As to my enthusiasm for a repeat of this experiment: not so much.

Free trade is, at the minimum, a two-way street, and then as now not all frictions had their genesis in US policy; France instituted protectionist tariffs two years before Smoot-Hawley. The present constellation of pacts does leave much to be desired and the candidates are not wrong in pointing out scope for change. Yet it’s hard to argue with the benefits of trade for America’s consumers, firms and workforce, still arguably the most competitive on earth.

That said, US workers and those of the developed nations are likely to be increasingly uncompetitive in low-wage, low-skill jobs tied to export, regardless of tariffs. Indeed, only through greater automation will the industries now dependent on that labor be able to meet the challenge of the developing world, and while such technology can create many jobs, they are likely to be much more highly skilled.

And that’s the point: the US is facing a serious shortage of skilled workers which could take on the dimensions of crisis in the next decade. Indeed, the 2015 Manpower Group survey already finds openings for skilled trade workers to be the hardest to fill. One can infer from Bureau of Labor Statistics estimates that, as the economy expands and Baby Boomers retire, by 2022 the US could require north of 240,000 new plumbers alone. The figure for electricians exceeds 110,000, and figures in construction, telecom and other trades are of a similar order. This labor cannot be easily outsourced, and, as remarkable as machine learning and robotics are, trust me: it’s going to be a while before a Roomba shows up at your door to unclog your toilet.

Moreover, both candidates have proposed substantial infrastructure restoration and expansion. This would only exacerbate excess demand for skilled trades. Note these jobs generally pay well above the minimum wage; in some cases, such as machinists, into six figures.

Yet there has been very little in the way of proposals to encourage training in these trades. Because they are increasingly technical, such education requires literacy and some mathematical skills, as well as specialized knowledge. This means substantial investment, and here there is room for innovative solutions parts of which could appeal to both sides of the aisle. For example, corporations requiring skilled labor could trade wage guarantees for unions “opening the books” to increase the number of workers. Government assistance in the form of financial aid for education and, in some cases. relocation could be financed by Treasury borrowing against anticipated tax revenue from both the workers and the enterprises employing them, who in turn could be incentivized to provide expanded training through tax breaks and contracts on infrastructure projects themselves.

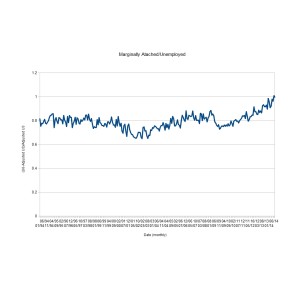

Skilled employment is not the solution to all of the problems of trade-displaced labor. Many of the careers discussed above are physically demanding and the training is extensive, making it very challenging for older laid-off workers to transition into them. However, this does represent a substantial opportunity for displaced younger workers, especially non-college grads, and a chance to decrease the stubbornly high underemployment rate (see “U6 Stalks The Hawk”) while safeguarding growth.

As for the bipartisanship necessary to implement something like this, it seems at least as likely as, say, a former host of “PM Magazine – Providence, RI” becoming the inquisitor faced by the two people vying for the leadership of the free world.

*Yes, that’s sarcasm.